Dec 28, 2025

Dec 28, 2025

Collaborative Ecosystems in Water Management

Sustainability Strategy

Sustainability Strategy

In This Article

Explores governance, implementation, and hybrid models in U.S. water management—trade-offs, measurable impacts, and data tools for fair, scalable outcomes.

Collaborative Ecosystems in Water Management

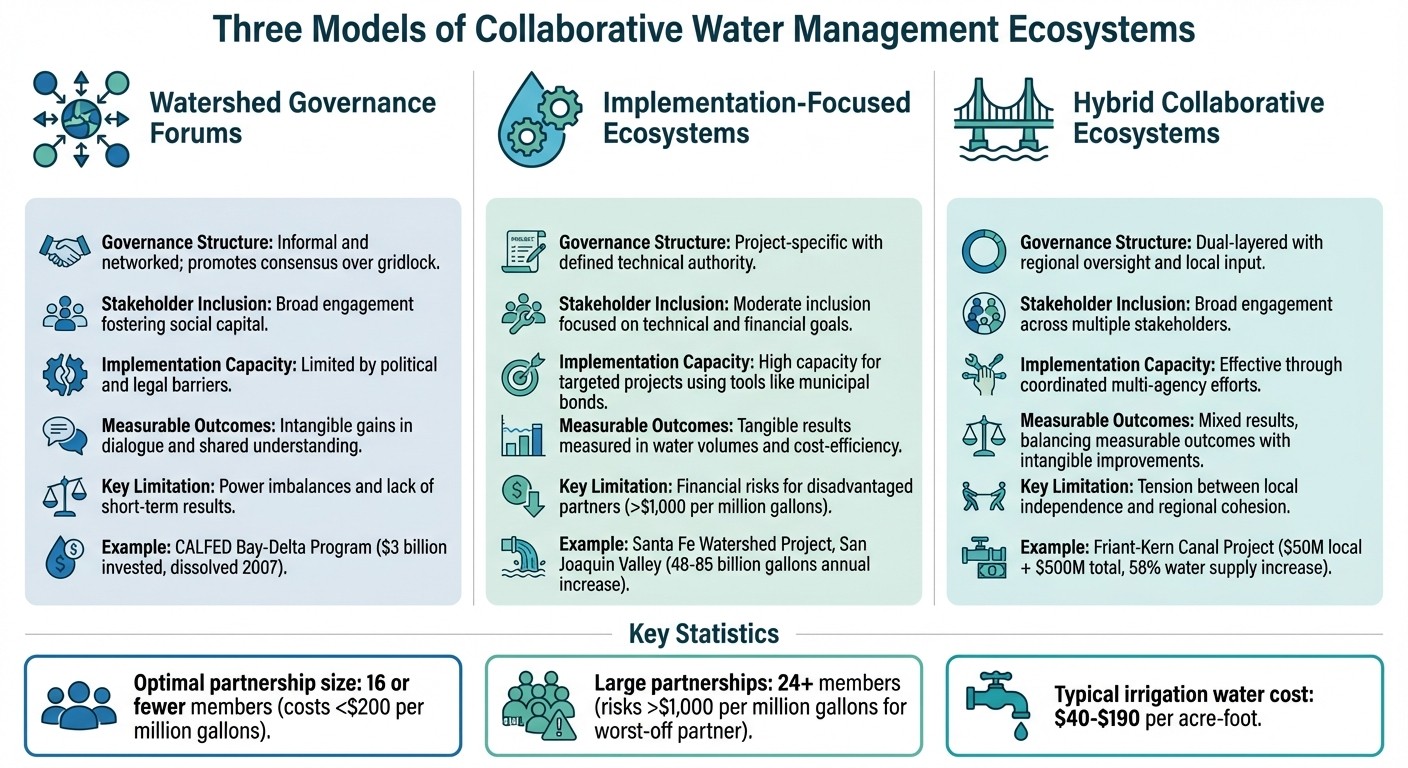

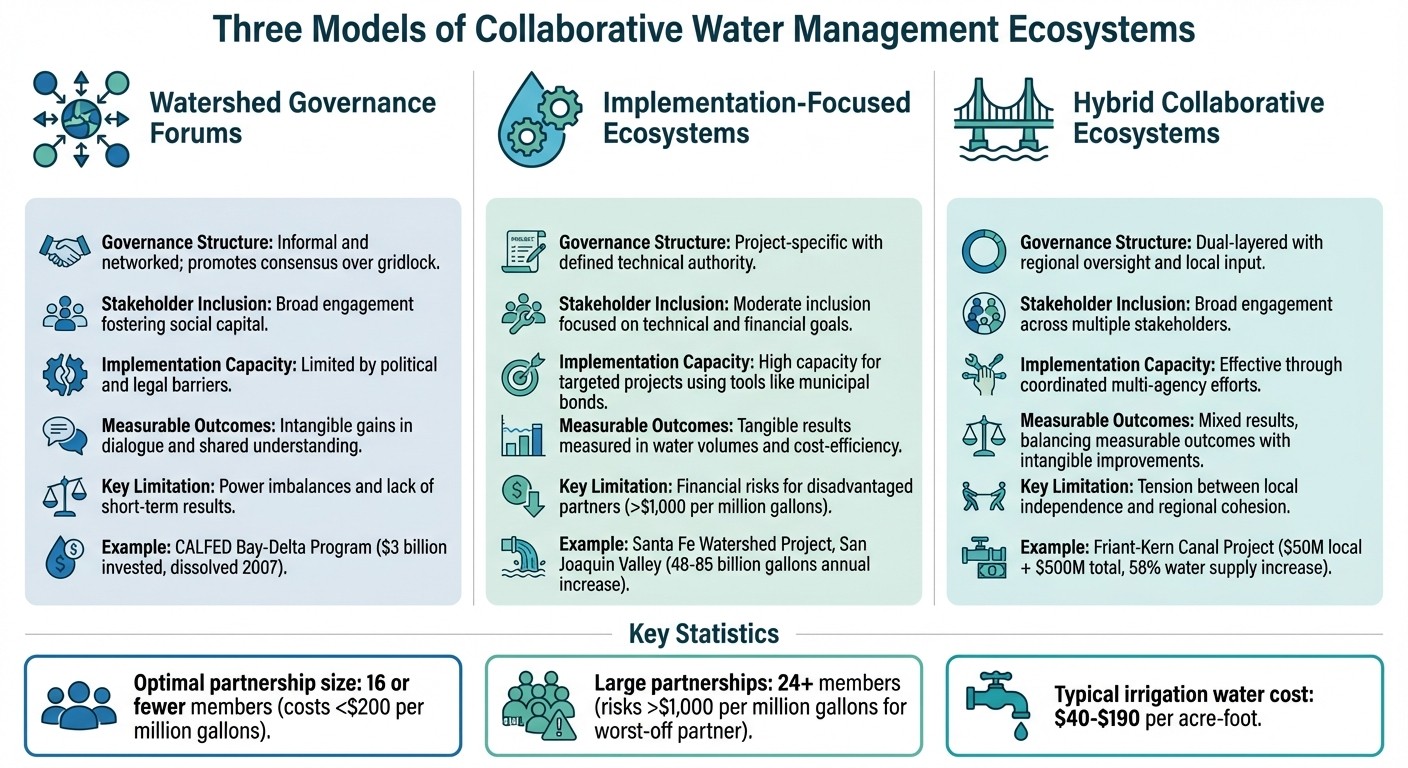

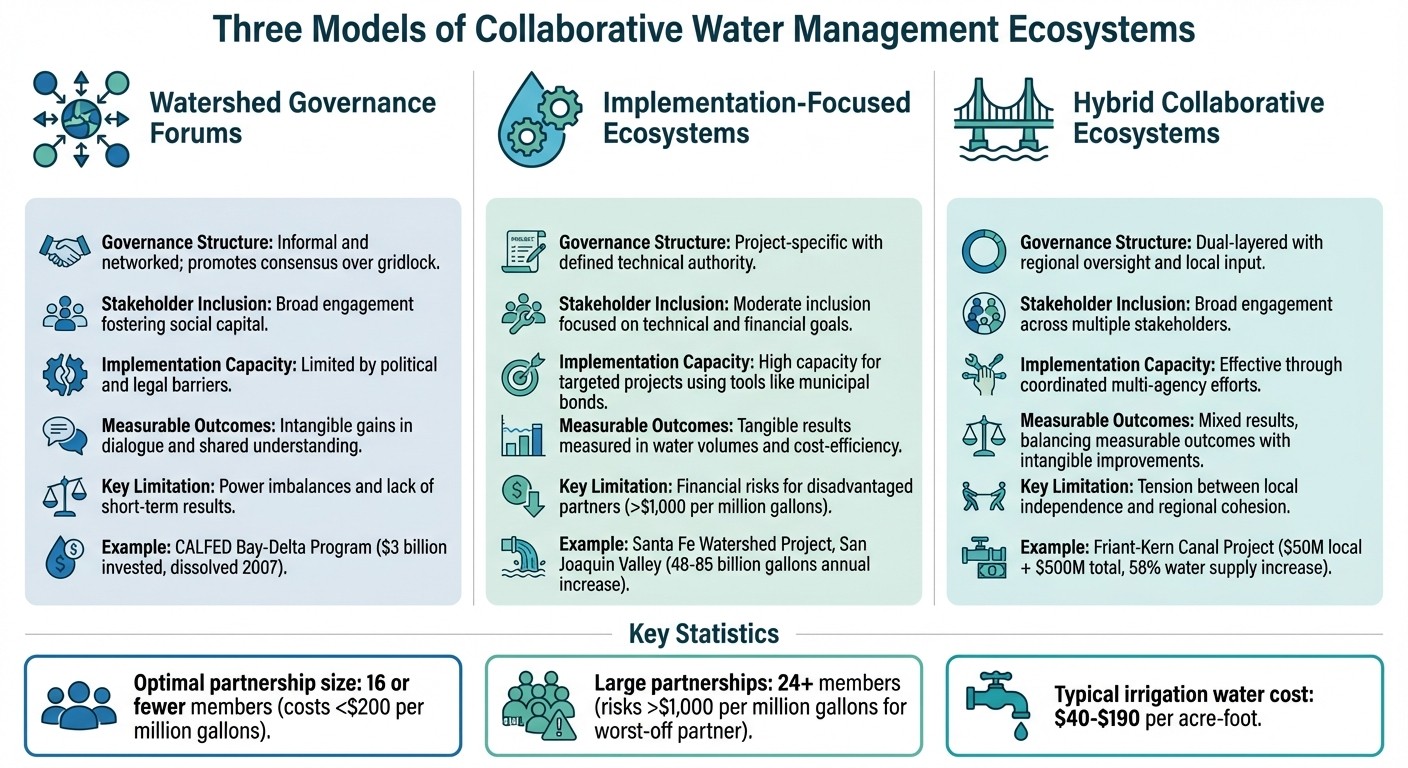

Water management in the U.S. faces growing challenges like climate extremes, aging infrastructure, and disputes over allocation. Traditional governance methods often fail due to fragmented oversight across jurisdictions. Collaborative ecosystems - multi-stakeholder partnerships - offer a solution by pooling resources, expertise, and efforts to address these issues. Three models have emerged:

Governance Forums: Focus on policy coordination and stakeholder consensus, such as California's CALFED Bay-Delta Program.

Implementation-Focused Models: Prioritize direct infrastructure projects and measurable results, like the Santa Fe Watershed Project.

Hybrid Approaches: Combine policy coordination with actionable projects, blending regional oversight with local execution.

Each model has strengths and limitations. Governance forums excel in building trust but struggle with delivering measurable results. Implementation models achieve clear outcomes but risk financial burdens for smaller partners. Hybrid systems balance these approaches but face challenges in scaling and resolving conflicts. Effective water management requires carefully structured partnerships, clear goals, and data-driven tools to address diverse stakeholder needs while optimizing outcomes.

Collaborative Approaches to Foster Groundwater Sustainability

1. Watershed Governance Forums

Watershed governance forums aim to coordinate policies and foster agreement among diverse stakeholders. Rather than managing infrastructure directly, they focus on creating collaborative frameworks. The CALFED Bay-Delta Program serves as a prime example of this approach, showcasing an adaptable structure and broad inclusivity that supports effective watershed management.

Governance Structure

These forums move away from rigid, top-down decision-making in favor of more adaptable and responsive systems. As Judith E. Innes, a professor at UC Berkeley, explains:

"Collaborative processes replaced gridlock and litigation through a balanced, comprehensive framework."

The governance structure of CALFED addressed the water needs of 35 million people by transitioning from a slow, rule-heavy bureaucracy to a more agile decision-making model. This shift allowed the program to respond promptly to dynamic conditions, such as changes in fishery health or weather patterns [6]. One notable achievement was the creation of the "Environmental Water Account", which safeguarded fish populations while ensuring water supply reliability [6].

Stakeholder Inclusion

CALFED brought together agricultural, urban, environmental, and governmental stakeholders, fostering cooperation among groups that were often at odds. By involving all parties, the program built what Innes describes as "social and political capital among previously warring parties" [6]. This inclusive strategy was critical in managing the San Francisco Bay-Delta, a critical water source for nearly two-thirds of California's population [6].

Implementation Capacity

Despite its collaborative successes, transitioning from traditional management to this new governance model presented challenges, particularly in delivering immediate, measurable results. CALFED invested $3 billion in various initiatives, including $1 billion dedicated to environmental restoration [3]. However, the program dissolved by 2007, largely because it struggled to deliver the kind of tangible outcomes that legislators, relying on traditional performance metrics, expected [3][6]. Giorgos Kallis, an ICREA Fellow, highlights this tension:

"While collaborative governance enhances mutual understandings and can be a source of innovation, it appears ill‐suited to resolve alone the distributive dilemmas at the core of many water - and other environmental - conflicts" [3].

Measurable Outcomes

Although consensus-building is essential, achieving measurable results remains a persistent challenge for governance forums. CALFED made strides in improving data quality by replacing agency-specific science with independent scientific reviews, which helped reduce disputes over technical information [6]. It also broke through stalemates and expedited decisions during crises [6]. However, these successes - while significant in terms of building trust and cooperation - do not easily align with the performance metrics demanded by funding agencies, creating ongoing challenges for program sustainability [6][7].

2. Implementation-Focused Ecosystems

In the face of fragmented water governance, implementation-focused ecosystems stand out by delivering practical, technical solutions. These systems focus on expanding water access, improving infrastructure, and restoring aquatic habitats. Unlike governance forums, which often emphasize dialogue and policy, these ecosystems prioritize measurable actions and operational efficiency.

Governance Structure

The governance models within these ecosystems are flexible and tailored to address specific challenges. They employ various approaches, including:

Informal Cooperation: Sharing resources like equipment without formal agreements.

Contractual Assistance: Hiring external services while maintaining overall control.

Joint Power Agencies: Creating new entities to manage shared responsibilities and resources.

Ownership Transfers: Consolidating systems under a single authority.

The choice of governance structure depends on the capacity and needs of the systems involved. For example, systems that want to retain control often opt for contractual assistance, while those facing similar challenges may form joint power agencies to pool expertise and resources.

Stakeholder Inclusion

Rather than relying on broad consensus, these ecosystems assign specific roles to keep projects on track. A prime example is the Santa Fe Watershed Project, where 28 experts from fields like biology, law, and engineering collaborated through a six-session workshop. They addressed issues such as wildfire risks, groundwater recharge uncertainties, and Tribal sovereignty. This effort revealed a post-fire debris flow probability exceeding 90% within the municipal watershed, directly influencing infrastructure priorities[9].

Implementation Capacity

These ecosystems enhance their operational capacity by fostering collaboration and resource-sharing. Partnerships between water systems allow for cost-saving measures like bulk purchasing, shared equipment use, and coordinated emergency responses. In Uganda, such initiatives successfully expanded water access to over 1 million people[10].

Measurable Outcomes

One of the strengths of implementation-focused ecosystems is their ability to deliver tangible, measurable results. For instance, they have generated ecosystem services valued at over $2 billion and increased local investment willingness[11][4]. In the Red River Basin, research identified 38 reservoirs classified as "Water Scarce", guiding strategic investments. The study also found that distributing conservation incentives across municipal, industrial, and agricultural sectors proved more cost-effective than focusing on a single sector[4].

As Thomas Neeson and his team at the University of Oklahoma and USGS observed:

"Small, collective reductions in human water use have the potential to generate large environmental benefits"[4].

These measurable outcomes highlight the efficiency of implementation-focused ecosystems in addressing water-related challenges and delivering impactful solutions.

3. Hybrid Collaborative Ecosystems

Hybrid collaborative ecosystems bring together the strengths of governance forums, which focus on consensus, and implementation ecosystems, which emphasize direct actions. By blending centralized oversight with local insights, these systems create layered governance frameworks that connect regional policies with on-the-ground efforts in water management [12]. This approach draws from the successes of both models to deliver results that are both practical and measurable.

Governance Structure

At the heart of hybrid systems lies a "dual-layered" governance structure. Broad policy directives are set at higher levels, while local stakeholders contribute specific implementation strategies and research priorities [9]. This setup helps bridge the gap that often exists in traditional water management, where centralized agencies may lack a full understanding of local conditions. A case in point is California's CALFED Bay-Delta Program. What began as an informal memorandum in 1994 evolved into a formal oversight authority by 2004, showing how adaptable frameworks can foster effective collaboration. Judith E. Innes of UC Berkeley highlighted this shift:

"Collaborative processes have replaced gridlock and litigation; a comprehensive framework with linkages and balance among activities replaced project-by-project decisions" [6].

Stakeholder Inclusion

One of the defining features of hybrid ecosystems is their inclusive approach to stakeholder participation. For example, CALFED brought together a diverse group that included urban water users, agricultural representatives, environmental NGOs, business leaders, tribal nations, and local residents [5, 11]. This broad participation builds the social and political capital needed to break through the deadlocks that often hinder traditional bureaucratic systems. In New Mexico, a recent project showcased the value of multi-disciplinary collaboration, involving experts from over 15 fields such as hydrology, law, journalism, and social psychology [9].

Implementation Capacity

Hybrid systems excel at turning discussions into action without sacrificing local autonomy. Coordinated regional efforts help avoid the decision-making paralysis that can plague large-scale projects. For example, TreePeople's Multi-Agency Collaborative in Los Angeles brought together agencies like the LA Department of Water and Power, the City of LA Bureau of Sanitation, and the LA County Department of Public Works. According to TreePeople:

"The collaborative governance approach brings agencies together for opportunities that previously would be hindered by bureaucratic silos" [8].

Another example is the Friant-Kern Canal Rehabilitation Project in California's San Joaquin Valley. The canal, which had lost up to 60% of its capacity due to land subsidence, benefited from a hybrid funding model. In 2021, the Friant Contractors - a group of local water providers - committed approximately $50 million to a $500 million rehabilitation effort, demonstrating how local and state-level investments can align effectively [2].

Measurable Outcomes

The results achieved by hybrid models often surpass those of purely governance- or implementation-focused approaches. In California's San Joaquin Valley, hybrid strategies using intelligent search algorithms increased water supply gains by 58% compared to traditional ad hoc methods, while also reducing financial risks [2]. This region, which supports 4 million people and 5 million acres of farmland, benefited from a combination of infrastructure investments. In the Tulare Lake Basin, 83% of optimal partnerships paired canal expansion with groundwater banking, increasing surface water deliveries by 48 to 85 billion gallons annually [2].

However, scalability introduces challenges. Larger partnerships, involving more than 24 members, achieved the highest overall water supply but sometimes left the "worst-off" partner with financial risks exceeding $1,000 per million gallons. In contrast, smaller partnerships with 16 or fewer members kept costs below $200 per million gallons. Considering that water providers in the San Joaquin Valley typically charge $40 to $190 per acre-foot for irrigation water, managing costs remains a critical priority [2].

Strengths and Limitations

Comparison of Three Water Management Collaborative Models: Governance, Implementation, and Hybrid Approaches

Examining the collaborative models outlined earlier, each approach brings distinct advantages and faces unique challenges. For instance, watershed governance forums are particularly effective at fostering trust and overcoming political stalemates. However, they often grapple with power imbalances, where more influential stakeholders dominate, leaving those focused on socio-environmental concerns with less influence in the conversation [1]. A stark example of such challenges is CALFED, which, despite a $3 billion investment in restoration and research, was dissolved in 2007 due to its inability to deliver clear, short-term results [3].

Implementation-focused ecosystems, on the other hand, prioritize technical expertise and disciplined budgeting to achieve measurable outcomes. A case in point is California's San Joaquin Valley, where infrastructure partnerships boosted annual surface water deliveries by an impressive 48 to 85 billion gallons [2]. However, these systems are not without flaws. Financial risks pose a significant challenge, as the least advantaged partners sometimes faced costs exceeding $1,000 per million gallons [2]. While this model excels at delivering quantifiable gains, its narrow focus on technical objectives often limits broader community involvement.

Hybrid collaborative ecosystems attempt to merge the strengths of both governance and implementation models by combining regional policies with localized execution. Yet, they also inherit the weaknesses of each approach. One recurring issue is the "biophysical realism gap", which reflects the disconnect between collaborative planning efforts and tangible, on-the-ground results [11]. Additionally, these ecosystems struggle to address deep-rooted distributive conflicts in water management [3]. Another persistent hurdle is balancing local autonomy with the need for cohesive regional action [12].

To provide a clearer perspective, the following table compares the key attributes of these models:

Dimension | Watershed Governance Forums | Implementation-Focused Ecosystems | Hybrid Collaborative Ecosystems |

|---|---|---|---|

Governance Structure | Informal and networked; promotes consensus over gridlock [6] | Project-specific with defined technical authority [2] | Dual-layered with regional oversight and local input [12] |

Stakeholder Inclusion | Broad engagement fostering social capital [3] | Moderate inclusion focused on technical and financial goals [2] | Broad engagement across multiple stakeholders [6] |

Implementation Capacity | Limited by political and legal barriers [6] | High capacity for targeted projects using tools like municipal bonds [2] | Effective through coordinated multi-agency efforts [12] |

Measurable Outcomes | Intangible gains in dialogue and shared understanding [6] | Tangible results measured in water volumes and cost-efficiency [2] | Mixed results, balancing measurable outcomes with intangible improvements [6] |

Key Limitation | Financial risks for disadvantaged partners [2] | Tension between local independence and regional cohesion [12] |

Conclusion

Each model for water management comes with its own set of trade-offs. Governance forums are particularly effective at fostering trust and encouraging dialogue, yet they often falter when it comes to resolving disputes over fair water distribution. As researchers Giorgos Kallis and Richard Norgaard have pointed out, collaborative governance alone cannot completely address these deep-seated conflicts [3].

On the other hand, implementation models prioritize measurable outcomes. For instance, infrastructure partnerships in the Tulare Lake Basin have achieved notable improvements in water supply [2]. However, these gains often come at a steep cost - over $1,000 per million gallons for underprivileged partners - raising serious equity concerns [2].

Striking the right balance in partnerships is key. Research indicates that partnerships with 16 or fewer members tend to maintain costs below $200 per million gallons. In contrast, those with 24 or more members frequently impose significant financial burdens on at least one partner [2]. This highlights the close relationship between partnership size and financial risk. Additionally, infrastructure projects designed to maximize partner benefits can inadvertently reduce water availability for non-partners, potentially leading to legal disputes that double transaction costs [2].

Advanced modeling tools offer a way to optimize partnership outcomes. A clear example comes from the Friant Contractors' $50 million investment in the Friant-Kern Canal rehabilitation in 2021. Using sophisticated modeling, alternative partnership structures were identified that delivered 58% greater water gains while reducing financial risks [2]. This underscores the critical role of data-driven tools in crafting effective partnership strategies.

Such tools turn complex design insights into actionable plans. Firms like Council Fire play an essential role in these efforts by providing the technical expertise needed to evaluate thousands of partnership scenarios. They utilize network analytics to pinpoint high-impact management opportunities and facilitate stakeholder collaboration across various levels, from consultation to co-creation [5]. By aligning financial goals with environmental and social priorities, these consultancies help organizations turn ambitious sustainability plans into practical, measurable results.

The key lies in setting realistic goals and adopting a middle-out modeling approach that balances strategic vision with technical precision. Organizations that emphasize inclusivity, proactively address third-party impacts, and leverage advanced analytics can create more resilient and equitable water management systems. These systems are better equipped to handle the challenges of climate uncertainty and meet the evolving needs of diverse stakeholders.

FAQs

What are the key differences between governance forums, implementation-focused ecosystems, and hybrid collaborative ecosystems in water management?

Governance forums serve as essential platforms where policymakers, regulators, and influential stakeholders come together to align on shared objectives, establish legal frameworks, and delegate responsibilities. These forums emphasize strategy, accountability, and open communication rather than hands-on project management. They typically operate under formal agreements or regulations, ensuring a structured approach to collaboration.

On the other hand, implementation-focused ecosystems operate at a more hands-on level. These bring together agencies, nonprofits, and private organizations to carry out specific initiatives, such as watershed restoration or stormwater management projects. Success in these ecosystems is gauged through measurable results, defined timelines, and performance indicators. Partnerships within these groups often evolve as individual projects are completed, reflecting their dynamic nature.

Hybrid collaborative ecosystems merge the strategic focus of governance forums with the operational strength of implementation ecosystems. These partnerships foster shared decision-making within project teams, allowing for a balanced approach to resource allocation, risk management, and financing. By integrating these elements, they work toward practical, long-term water solutions. Organizations like Council Fire play a pivotal role in these ecosystems, bridging the gap between policy objectives and actionable projects while ensuring that environmental, social, and financial goals are addressed cohesively.

How do collaborative ecosystems help smaller partners manage financial risks in water management projects?

Collaborative ecosystems in water management projects provide a safety net for smaller partners by spreading costs and responsibilities among public, private, and community stakeholders. This shared framework ensures no single entity shoulders the entire financial burden, making it more feasible for smaller organizations to engage and contribute.

Key strategies within these partnerships include tiered financing mechanisms, such as low-interest loans, grants, or repayment plans tied to revenue. Additionally, regionalization strategies play a vital role by pooling resources from multiple communities, creating efficiencies that reduce costs. Public-private partnerships (P3s) are another effective model, offering access to external funding, technical expertise, and steady revenue streams. These partnerships enable smaller utilities to upgrade infrastructure and meet regulatory standards without overwhelming their budgets.

Council Fire works with organizations to navigate these collaborative ecosystems by facilitating stakeholder engagement, aligning financial goals, and crafting communication strategies that highlight mutual benefits. This approach helps ensure smaller partners maintain financial stability while actively contributing to more sustainable and resilient water systems.

How do data-driven tools enhance collaboration in water management partnerships?

Data-driven tools are reshaping how water management partners work together by turning fragmented information into clear, actionable insights. These tools make it possible to monitor water supplies, identify problems, and evaluate conservation efforts in real time, promoting both transparency and efficiency across the board.

Technologies such as modeling systems and decision-support platforms are particularly valuable in assessing potential collaborations. They provide insights into compliance challenges, weigh cost-benefit scenarios, and evaluate risks, helping stakeholders make informed decisions. Additionally, these tools enable the exploration of solutions that effectively balance financial considerations with responsible water resource management. By adopting these technologies, organizations can forge stronger, more adaptable partnerships that align environmental priorities with sustainable long-term outcomes.

Related Blog Posts

Latest Articles

©2025

FAQ

FAQ

01

What does a project look like?

02

How is the pricing structure?

03

Are all projects fixed scope?

04

What is the ROI?

05

How do we measure success?

06

What do I need to get started?

07

How easy is it to edit for beginners?

08

Do I need to know how to code?

01

What does a project look like?

02

How is the pricing structure?

03

Are all projects fixed scope?

04

What is the ROI?

05

How do we measure success?

06

What do I need to get started?

07

How easy is it to edit for beginners?

08

Do I need to know how to code?

Dec 28, 2025

Collaborative Ecosystems in Water Management

Sustainability Strategy

In This Article

Explores governance, implementation, and hybrid models in U.S. water management—trade-offs, measurable impacts, and data tools for fair, scalable outcomes.

Collaborative Ecosystems in Water Management

Water management in the U.S. faces growing challenges like climate extremes, aging infrastructure, and disputes over allocation. Traditional governance methods often fail due to fragmented oversight across jurisdictions. Collaborative ecosystems - multi-stakeholder partnerships - offer a solution by pooling resources, expertise, and efforts to address these issues. Three models have emerged:

Governance Forums: Focus on policy coordination and stakeholder consensus, such as California's CALFED Bay-Delta Program.

Implementation-Focused Models: Prioritize direct infrastructure projects and measurable results, like the Santa Fe Watershed Project.

Hybrid Approaches: Combine policy coordination with actionable projects, blending regional oversight with local execution.

Each model has strengths and limitations. Governance forums excel in building trust but struggle with delivering measurable results. Implementation models achieve clear outcomes but risk financial burdens for smaller partners. Hybrid systems balance these approaches but face challenges in scaling and resolving conflicts. Effective water management requires carefully structured partnerships, clear goals, and data-driven tools to address diverse stakeholder needs while optimizing outcomes.

Collaborative Approaches to Foster Groundwater Sustainability

1. Watershed Governance Forums

Watershed governance forums aim to coordinate policies and foster agreement among diverse stakeholders. Rather than managing infrastructure directly, they focus on creating collaborative frameworks. The CALFED Bay-Delta Program serves as a prime example of this approach, showcasing an adaptable structure and broad inclusivity that supports effective watershed management.

Governance Structure

These forums move away from rigid, top-down decision-making in favor of more adaptable and responsive systems. As Judith E. Innes, a professor at UC Berkeley, explains:

"Collaborative processes replaced gridlock and litigation through a balanced, comprehensive framework."

The governance structure of CALFED addressed the water needs of 35 million people by transitioning from a slow, rule-heavy bureaucracy to a more agile decision-making model. This shift allowed the program to respond promptly to dynamic conditions, such as changes in fishery health or weather patterns [6]. One notable achievement was the creation of the "Environmental Water Account", which safeguarded fish populations while ensuring water supply reliability [6].

Stakeholder Inclusion

CALFED brought together agricultural, urban, environmental, and governmental stakeholders, fostering cooperation among groups that were often at odds. By involving all parties, the program built what Innes describes as "social and political capital among previously warring parties" [6]. This inclusive strategy was critical in managing the San Francisco Bay-Delta, a critical water source for nearly two-thirds of California's population [6].

Implementation Capacity

Despite its collaborative successes, transitioning from traditional management to this new governance model presented challenges, particularly in delivering immediate, measurable results. CALFED invested $3 billion in various initiatives, including $1 billion dedicated to environmental restoration [3]. However, the program dissolved by 2007, largely because it struggled to deliver the kind of tangible outcomes that legislators, relying on traditional performance metrics, expected [3][6]. Giorgos Kallis, an ICREA Fellow, highlights this tension:

"While collaborative governance enhances mutual understandings and can be a source of innovation, it appears ill‐suited to resolve alone the distributive dilemmas at the core of many water - and other environmental - conflicts" [3].

Measurable Outcomes

Although consensus-building is essential, achieving measurable results remains a persistent challenge for governance forums. CALFED made strides in improving data quality by replacing agency-specific science with independent scientific reviews, which helped reduce disputes over technical information [6]. It also broke through stalemates and expedited decisions during crises [6]. However, these successes - while significant in terms of building trust and cooperation - do not easily align with the performance metrics demanded by funding agencies, creating ongoing challenges for program sustainability [6][7].

2. Implementation-Focused Ecosystems

In the face of fragmented water governance, implementation-focused ecosystems stand out by delivering practical, technical solutions. These systems focus on expanding water access, improving infrastructure, and restoring aquatic habitats. Unlike governance forums, which often emphasize dialogue and policy, these ecosystems prioritize measurable actions and operational efficiency.

Governance Structure

The governance models within these ecosystems are flexible and tailored to address specific challenges. They employ various approaches, including:

Informal Cooperation: Sharing resources like equipment without formal agreements.

Contractual Assistance: Hiring external services while maintaining overall control.

Joint Power Agencies: Creating new entities to manage shared responsibilities and resources.

Ownership Transfers: Consolidating systems under a single authority.

The choice of governance structure depends on the capacity and needs of the systems involved. For example, systems that want to retain control often opt for contractual assistance, while those facing similar challenges may form joint power agencies to pool expertise and resources.

Stakeholder Inclusion

Rather than relying on broad consensus, these ecosystems assign specific roles to keep projects on track. A prime example is the Santa Fe Watershed Project, where 28 experts from fields like biology, law, and engineering collaborated through a six-session workshop. They addressed issues such as wildfire risks, groundwater recharge uncertainties, and Tribal sovereignty. This effort revealed a post-fire debris flow probability exceeding 90% within the municipal watershed, directly influencing infrastructure priorities[9].

Implementation Capacity

These ecosystems enhance their operational capacity by fostering collaboration and resource-sharing. Partnerships between water systems allow for cost-saving measures like bulk purchasing, shared equipment use, and coordinated emergency responses. In Uganda, such initiatives successfully expanded water access to over 1 million people[10].

Measurable Outcomes

One of the strengths of implementation-focused ecosystems is their ability to deliver tangible, measurable results. For instance, they have generated ecosystem services valued at over $2 billion and increased local investment willingness[11][4]. In the Red River Basin, research identified 38 reservoirs classified as "Water Scarce", guiding strategic investments. The study also found that distributing conservation incentives across municipal, industrial, and agricultural sectors proved more cost-effective than focusing on a single sector[4].

As Thomas Neeson and his team at the University of Oklahoma and USGS observed:

"Small, collective reductions in human water use have the potential to generate large environmental benefits"[4].

These measurable outcomes highlight the efficiency of implementation-focused ecosystems in addressing water-related challenges and delivering impactful solutions.

3. Hybrid Collaborative Ecosystems

Hybrid collaborative ecosystems bring together the strengths of governance forums, which focus on consensus, and implementation ecosystems, which emphasize direct actions. By blending centralized oversight with local insights, these systems create layered governance frameworks that connect regional policies with on-the-ground efforts in water management [12]. This approach draws from the successes of both models to deliver results that are both practical and measurable.

Governance Structure

At the heart of hybrid systems lies a "dual-layered" governance structure. Broad policy directives are set at higher levels, while local stakeholders contribute specific implementation strategies and research priorities [9]. This setup helps bridge the gap that often exists in traditional water management, where centralized agencies may lack a full understanding of local conditions. A case in point is California's CALFED Bay-Delta Program. What began as an informal memorandum in 1994 evolved into a formal oversight authority by 2004, showing how adaptable frameworks can foster effective collaboration. Judith E. Innes of UC Berkeley highlighted this shift:

"Collaborative processes have replaced gridlock and litigation; a comprehensive framework with linkages and balance among activities replaced project-by-project decisions" [6].

Stakeholder Inclusion

One of the defining features of hybrid ecosystems is their inclusive approach to stakeholder participation. For example, CALFED brought together a diverse group that included urban water users, agricultural representatives, environmental NGOs, business leaders, tribal nations, and local residents [5, 11]. This broad participation builds the social and political capital needed to break through the deadlocks that often hinder traditional bureaucratic systems. In New Mexico, a recent project showcased the value of multi-disciplinary collaboration, involving experts from over 15 fields such as hydrology, law, journalism, and social psychology [9].

Implementation Capacity

Hybrid systems excel at turning discussions into action without sacrificing local autonomy. Coordinated regional efforts help avoid the decision-making paralysis that can plague large-scale projects. For example, TreePeople's Multi-Agency Collaborative in Los Angeles brought together agencies like the LA Department of Water and Power, the City of LA Bureau of Sanitation, and the LA County Department of Public Works. According to TreePeople:

"The collaborative governance approach brings agencies together for opportunities that previously would be hindered by bureaucratic silos" [8].

Another example is the Friant-Kern Canal Rehabilitation Project in California's San Joaquin Valley. The canal, which had lost up to 60% of its capacity due to land subsidence, benefited from a hybrid funding model. In 2021, the Friant Contractors - a group of local water providers - committed approximately $50 million to a $500 million rehabilitation effort, demonstrating how local and state-level investments can align effectively [2].

Measurable Outcomes

The results achieved by hybrid models often surpass those of purely governance- or implementation-focused approaches. In California's San Joaquin Valley, hybrid strategies using intelligent search algorithms increased water supply gains by 58% compared to traditional ad hoc methods, while also reducing financial risks [2]. This region, which supports 4 million people and 5 million acres of farmland, benefited from a combination of infrastructure investments. In the Tulare Lake Basin, 83% of optimal partnerships paired canal expansion with groundwater banking, increasing surface water deliveries by 48 to 85 billion gallons annually [2].

However, scalability introduces challenges. Larger partnerships, involving more than 24 members, achieved the highest overall water supply but sometimes left the "worst-off" partner with financial risks exceeding $1,000 per million gallons. In contrast, smaller partnerships with 16 or fewer members kept costs below $200 per million gallons. Considering that water providers in the San Joaquin Valley typically charge $40 to $190 per acre-foot for irrigation water, managing costs remains a critical priority [2].

Strengths and Limitations

Comparison of Three Water Management Collaborative Models: Governance, Implementation, and Hybrid Approaches

Examining the collaborative models outlined earlier, each approach brings distinct advantages and faces unique challenges. For instance, watershed governance forums are particularly effective at fostering trust and overcoming political stalemates. However, they often grapple with power imbalances, where more influential stakeholders dominate, leaving those focused on socio-environmental concerns with less influence in the conversation [1]. A stark example of such challenges is CALFED, which, despite a $3 billion investment in restoration and research, was dissolved in 2007 due to its inability to deliver clear, short-term results [3].

Implementation-focused ecosystems, on the other hand, prioritize technical expertise and disciplined budgeting to achieve measurable outcomes. A case in point is California's San Joaquin Valley, where infrastructure partnerships boosted annual surface water deliveries by an impressive 48 to 85 billion gallons [2]. However, these systems are not without flaws. Financial risks pose a significant challenge, as the least advantaged partners sometimes faced costs exceeding $1,000 per million gallons [2]. While this model excels at delivering quantifiable gains, its narrow focus on technical objectives often limits broader community involvement.

Hybrid collaborative ecosystems attempt to merge the strengths of both governance and implementation models by combining regional policies with localized execution. Yet, they also inherit the weaknesses of each approach. One recurring issue is the "biophysical realism gap", which reflects the disconnect between collaborative planning efforts and tangible, on-the-ground results [11]. Additionally, these ecosystems struggle to address deep-rooted distributive conflicts in water management [3]. Another persistent hurdle is balancing local autonomy with the need for cohesive regional action [12].

To provide a clearer perspective, the following table compares the key attributes of these models:

Dimension | Watershed Governance Forums | Implementation-Focused Ecosystems | Hybrid Collaborative Ecosystems |

|---|---|---|---|

Governance Structure | Informal and networked; promotes consensus over gridlock [6] | Project-specific with defined technical authority [2] | Dual-layered with regional oversight and local input [12] |

Stakeholder Inclusion | Broad engagement fostering social capital [3] | Moderate inclusion focused on technical and financial goals [2] | Broad engagement across multiple stakeholders [6] |

Implementation Capacity | Limited by political and legal barriers [6] | High capacity for targeted projects using tools like municipal bonds [2] | Effective through coordinated multi-agency efforts [12] |

Measurable Outcomes | Intangible gains in dialogue and shared understanding [6] | Tangible results measured in water volumes and cost-efficiency [2] | Mixed results, balancing measurable outcomes with intangible improvements [6] |

Key Limitation | Financial risks for disadvantaged partners [2] | Tension between local independence and regional cohesion [12] |

Conclusion

Each model for water management comes with its own set of trade-offs. Governance forums are particularly effective at fostering trust and encouraging dialogue, yet they often falter when it comes to resolving disputes over fair water distribution. As researchers Giorgos Kallis and Richard Norgaard have pointed out, collaborative governance alone cannot completely address these deep-seated conflicts [3].

On the other hand, implementation models prioritize measurable outcomes. For instance, infrastructure partnerships in the Tulare Lake Basin have achieved notable improvements in water supply [2]. However, these gains often come at a steep cost - over $1,000 per million gallons for underprivileged partners - raising serious equity concerns [2].

Striking the right balance in partnerships is key. Research indicates that partnerships with 16 or fewer members tend to maintain costs below $200 per million gallons. In contrast, those with 24 or more members frequently impose significant financial burdens on at least one partner [2]. This highlights the close relationship between partnership size and financial risk. Additionally, infrastructure projects designed to maximize partner benefits can inadvertently reduce water availability for non-partners, potentially leading to legal disputes that double transaction costs [2].

Advanced modeling tools offer a way to optimize partnership outcomes. A clear example comes from the Friant Contractors' $50 million investment in the Friant-Kern Canal rehabilitation in 2021. Using sophisticated modeling, alternative partnership structures were identified that delivered 58% greater water gains while reducing financial risks [2]. This underscores the critical role of data-driven tools in crafting effective partnership strategies.

Such tools turn complex design insights into actionable plans. Firms like Council Fire play an essential role in these efforts by providing the technical expertise needed to evaluate thousands of partnership scenarios. They utilize network analytics to pinpoint high-impact management opportunities and facilitate stakeholder collaboration across various levels, from consultation to co-creation [5]. By aligning financial goals with environmental and social priorities, these consultancies help organizations turn ambitious sustainability plans into practical, measurable results.

The key lies in setting realistic goals and adopting a middle-out modeling approach that balances strategic vision with technical precision. Organizations that emphasize inclusivity, proactively address third-party impacts, and leverage advanced analytics can create more resilient and equitable water management systems. These systems are better equipped to handle the challenges of climate uncertainty and meet the evolving needs of diverse stakeholders.

FAQs

What are the key differences between governance forums, implementation-focused ecosystems, and hybrid collaborative ecosystems in water management?

Governance forums serve as essential platforms where policymakers, regulators, and influential stakeholders come together to align on shared objectives, establish legal frameworks, and delegate responsibilities. These forums emphasize strategy, accountability, and open communication rather than hands-on project management. They typically operate under formal agreements or regulations, ensuring a structured approach to collaboration.

On the other hand, implementation-focused ecosystems operate at a more hands-on level. These bring together agencies, nonprofits, and private organizations to carry out specific initiatives, such as watershed restoration or stormwater management projects. Success in these ecosystems is gauged through measurable results, defined timelines, and performance indicators. Partnerships within these groups often evolve as individual projects are completed, reflecting their dynamic nature.

Hybrid collaborative ecosystems merge the strategic focus of governance forums with the operational strength of implementation ecosystems. These partnerships foster shared decision-making within project teams, allowing for a balanced approach to resource allocation, risk management, and financing. By integrating these elements, they work toward practical, long-term water solutions. Organizations like Council Fire play a pivotal role in these ecosystems, bridging the gap between policy objectives and actionable projects while ensuring that environmental, social, and financial goals are addressed cohesively.

How do collaborative ecosystems help smaller partners manage financial risks in water management projects?

Collaborative ecosystems in water management projects provide a safety net for smaller partners by spreading costs and responsibilities among public, private, and community stakeholders. This shared framework ensures no single entity shoulders the entire financial burden, making it more feasible for smaller organizations to engage and contribute.

Key strategies within these partnerships include tiered financing mechanisms, such as low-interest loans, grants, or repayment plans tied to revenue. Additionally, regionalization strategies play a vital role by pooling resources from multiple communities, creating efficiencies that reduce costs. Public-private partnerships (P3s) are another effective model, offering access to external funding, technical expertise, and steady revenue streams. These partnerships enable smaller utilities to upgrade infrastructure and meet regulatory standards without overwhelming their budgets.

Council Fire works with organizations to navigate these collaborative ecosystems by facilitating stakeholder engagement, aligning financial goals, and crafting communication strategies that highlight mutual benefits. This approach helps ensure smaller partners maintain financial stability while actively contributing to more sustainable and resilient water systems.

How do data-driven tools enhance collaboration in water management partnerships?

Data-driven tools are reshaping how water management partners work together by turning fragmented information into clear, actionable insights. These tools make it possible to monitor water supplies, identify problems, and evaluate conservation efforts in real time, promoting both transparency and efficiency across the board.

Technologies such as modeling systems and decision-support platforms are particularly valuable in assessing potential collaborations. They provide insights into compliance challenges, weigh cost-benefit scenarios, and evaluate risks, helping stakeholders make informed decisions. Additionally, these tools enable the exploration of solutions that effectively balance financial considerations with responsible water resource management. By adopting these technologies, organizations can forge stronger, more adaptable partnerships that align environmental priorities with sustainable long-term outcomes.

Related Blog Posts

FAQ

01

What does a project look like?

02

How is the pricing structure?

03

Are all projects fixed scope?

04

What is the ROI?

05

How do we measure success?

06

What do I need to get started?

07

How easy is it to edit for beginners?

08

Do I need to know how to code?

Dec 28, 2025

Collaborative Ecosystems in Water Management

Sustainability Strategy

In This Article

Explores governance, implementation, and hybrid models in U.S. water management—trade-offs, measurable impacts, and data tools for fair, scalable outcomes.

Collaborative Ecosystems in Water Management

Water management in the U.S. faces growing challenges like climate extremes, aging infrastructure, and disputes over allocation. Traditional governance methods often fail due to fragmented oversight across jurisdictions. Collaborative ecosystems - multi-stakeholder partnerships - offer a solution by pooling resources, expertise, and efforts to address these issues. Three models have emerged:

Governance Forums: Focus on policy coordination and stakeholder consensus, such as California's CALFED Bay-Delta Program.

Implementation-Focused Models: Prioritize direct infrastructure projects and measurable results, like the Santa Fe Watershed Project.

Hybrid Approaches: Combine policy coordination with actionable projects, blending regional oversight with local execution.

Each model has strengths and limitations. Governance forums excel in building trust but struggle with delivering measurable results. Implementation models achieve clear outcomes but risk financial burdens for smaller partners. Hybrid systems balance these approaches but face challenges in scaling and resolving conflicts. Effective water management requires carefully structured partnerships, clear goals, and data-driven tools to address diverse stakeholder needs while optimizing outcomes.

Collaborative Approaches to Foster Groundwater Sustainability

1. Watershed Governance Forums

Watershed governance forums aim to coordinate policies and foster agreement among diverse stakeholders. Rather than managing infrastructure directly, they focus on creating collaborative frameworks. The CALFED Bay-Delta Program serves as a prime example of this approach, showcasing an adaptable structure and broad inclusivity that supports effective watershed management.

Governance Structure

These forums move away from rigid, top-down decision-making in favor of more adaptable and responsive systems. As Judith E. Innes, a professor at UC Berkeley, explains:

"Collaborative processes replaced gridlock and litigation through a balanced, comprehensive framework."

The governance structure of CALFED addressed the water needs of 35 million people by transitioning from a slow, rule-heavy bureaucracy to a more agile decision-making model. This shift allowed the program to respond promptly to dynamic conditions, such as changes in fishery health or weather patterns [6]. One notable achievement was the creation of the "Environmental Water Account", which safeguarded fish populations while ensuring water supply reliability [6].

Stakeholder Inclusion

CALFED brought together agricultural, urban, environmental, and governmental stakeholders, fostering cooperation among groups that were often at odds. By involving all parties, the program built what Innes describes as "social and political capital among previously warring parties" [6]. This inclusive strategy was critical in managing the San Francisco Bay-Delta, a critical water source for nearly two-thirds of California's population [6].

Implementation Capacity

Despite its collaborative successes, transitioning from traditional management to this new governance model presented challenges, particularly in delivering immediate, measurable results. CALFED invested $3 billion in various initiatives, including $1 billion dedicated to environmental restoration [3]. However, the program dissolved by 2007, largely because it struggled to deliver the kind of tangible outcomes that legislators, relying on traditional performance metrics, expected [3][6]. Giorgos Kallis, an ICREA Fellow, highlights this tension:

"While collaborative governance enhances mutual understandings and can be a source of innovation, it appears ill‐suited to resolve alone the distributive dilemmas at the core of many water - and other environmental - conflicts" [3].

Measurable Outcomes

Although consensus-building is essential, achieving measurable results remains a persistent challenge for governance forums. CALFED made strides in improving data quality by replacing agency-specific science with independent scientific reviews, which helped reduce disputes over technical information [6]. It also broke through stalemates and expedited decisions during crises [6]. However, these successes - while significant in terms of building trust and cooperation - do not easily align with the performance metrics demanded by funding agencies, creating ongoing challenges for program sustainability [6][7].

2. Implementation-Focused Ecosystems

In the face of fragmented water governance, implementation-focused ecosystems stand out by delivering practical, technical solutions. These systems focus on expanding water access, improving infrastructure, and restoring aquatic habitats. Unlike governance forums, which often emphasize dialogue and policy, these ecosystems prioritize measurable actions and operational efficiency.

Governance Structure

The governance models within these ecosystems are flexible and tailored to address specific challenges. They employ various approaches, including:

Informal Cooperation: Sharing resources like equipment without formal agreements.

Contractual Assistance: Hiring external services while maintaining overall control.

Joint Power Agencies: Creating new entities to manage shared responsibilities and resources.

Ownership Transfers: Consolidating systems under a single authority.

The choice of governance structure depends on the capacity and needs of the systems involved. For example, systems that want to retain control often opt for contractual assistance, while those facing similar challenges may form joint power agencies to pool expertise and resources.

Stakeholder Inclusion

Rather than relying on broad consensus, these ecosystems assign specific roles to keep projects on track. A prime example is the Santa Fe Watershed Project, where 28 experts from fields like biology, law, and engineering collaborated through a six-session workshop. They addressed issues such as wildfire risks, groundwater recharge uncertainties, and Tribal sovereignty. This effort revealed a post-fire debris flow probability exceeding 90% within the municipal watershed, directly influencing infrastructure priorities[9].

Implementation Capacity

These ecosystems enhance their operational capacity by fostering collaboration and resource-sharing. Partnerships between water systems allow for cost-saving measures like bulk purchasing, shared equipment use, and coordinated emergency responses. In Uganda, such initiatives successfully expanded water access to over 1 million people[10].

Measurable Outcomes

One of the strengths of implementation-focused ecosystems is their ability to deliver tangible, measurable results. For instance, they have generated ecosystem services valued at over $2 billion and increased local investment willingness[11][4]. In the Red River Basin, research identified 38 reservoirs classified as "Water Scarce", guiding strategic investments. The study also found that distributing conservation incentives across municipal, industrial, and agricultural sectors proved more cost-effective than focusing on a single sector[4].

As Thomas Neeson and his team at the University of Oklahoma and USGS observed:

"Small, collective reductions in human water use have the potential to generate large environmental benefits"[4].

These measurable outcomes highlight the efficiency of implementation-focused ecosystems in addressing water-related challenges and delivering impactful solutions.

3. Hybrid Collaborative Ecosystems

Hybrid collaborative ecosystems bring together the strengths of governance forums, which focus on consensus, and implementation ecosystems, which emphasize direct actions. By blending centralized oversight with local insights, these systems create layered governance frameworks that connect regional policies with on-the-ground efforts in water management [12]. This approach draws from the successes of both models to deliver results that are both practical and measurable.

Governance Structure

At the heart of hybrid systems lies a "dual-layered" governance structure. Broad policy directives are set at higher levels, while local stakeholders contribute specific implementation strategies and research priorities [9]. This setup helps bridge the gap that often exists in traditional water management, where centralized agencies may lack a full understanding of local conditions. A case in point is California's CALFED Bay-Delta Program. What began as an informal memorandum in 1994 evolved into a formal oversight authority by 2004, showing how adaptable frameworks can foster effective collaboration. Judith E. Innes of UC Berkeley highlighted this shift:

"Collaborative processes have replaced gridlock and litigation; a comprehensive framework with linkages and balance among activities replaced project-by-project decisions" [6].

Stakeholder Inclusion

One of the defining features of hybrid ecosystems is their inclusive approach to stakeholder participation. For example, CALFED brought together a diverse group that included urban water users, agricultural representatives, environmental NGOs, business leaders, tribal nations, and local residents [5, 11]. This broad participation builds the social and political capital needed to break through the deadlocks that often hinder traditional bureaucratic systems. In New Mexico, a recent project showcased the value of multi-disciplinary collaboration, involving experts from over 15 fields such as hydrology, law, journalism, and social psychology [9].

Implementation Capacity

Hybrid systems excel at turning discussions into action without sacrificing local autonomy. Coordinated regional efforts help avoid the decision-making paralysis that can plague large-scale projects. For example, TreePeople's Multi-Agency Collaborative in Los Angeles brought together agencies like the LA Department of Water and Power, the City of LA Bureau of Sanitation, and the LA County Department of Public Works. According to TreePeople:

"The collaborative governance approach brings agencies together for opportunities that previously would be hindered by bureaucratic silos" [8].

Another example is the Friant-Kern Canal Rehabilitation Project in California's San Joaquin Valley. The canal, which had lost up to 60% of its capacity due to land subsidence, benefited from a hybrid funding model. In 2021, the Friant Contractors - a group of local water providers - committed approximately $50 million to a $500 million rehabilitation effort, demonstrating how local and state-level investments can align effectively [2].

Measurable Outcomes

The results achieved by hybrid models often surpass those of purely governance- or implementation-focused approaches. In California's San Joaquin Valley, hybrid strategies using intelligent search algorithms increased water supply gains by 58% compared to traditional ad hoc methods, while also reducing financial risks [2]. This region, which supports 4 million people and 5 million acres of farmland, benefited from a combination of infrastructure investments. In the Tulare Lake Basin, 83% of optimal partnerships paired canal expansion with groundwater banking, increasing surface water deliveries by 48 to 85 billion gallons annually [2].

However, scalability introduces challenges. Larger partnerships, involving more than 24 members, achieved the highest overall water supply but sometimes left the "worst-off" partner with financial risks exceeding $1,000 per million gallons. In contrast, smaller partnerships with 16 or fewer members kept costs below $200 per million gallons. Considering that water providers in the San Joaquin Valley typically charge $40 to $190 per acre-foot for irrigation water, managing costs remains a critical priority [2].

Strengths and Limitations

Comparison of Three Water Management Collaborative Models: Governance, Implementation, and Hybrid Approaches

Examining the collaborative models outlined earlier, each approach brings distinct advantages and faces unique challenges. For instance, watershed governance forums are particularly effective at fostering trust and overcoming political stalemates. However, they often grapple with power imbalances, where more influential stakeholders dominate, leaving those focused on socio-environmental concerns with less influence in the conversation [1]. A stark example of such challenges is CALFED, which, despite a $3 billion investment in restoration and research, was dissolved in 2007 due to its inability to deliver clear, short-term results [3].

Implementation-focused ecosystems, on the other hand, prioritize technical expertise and disciplined budgeting to achieve measurable outcomes. A case in point is California's San Joaquin Valley, where infrastructure partnerships boosted annual surface water deliveries by an impressive 48 to 85 billion gallons [2]. However, these systems are not without flaws. Financial risks pose a significant challenge, as the least advantaged partners sometimes faced costs exceeding $1,000 per million gallons [2]. While this model excels at delivering quantifiable gains, its narrow focus on technical objectives often limits broader community involvement.

Hybrid collaborative ecosystems attempt to merge the strengths of both governance and implementation models by combining regional policies with localized execution. Yet, they also inherit the weaknesses of each approach. One recurring issue is the "biophysical realism gap", which reflects the disconnect between collaborative planning efforts and tangible, on-the-ground results [11]. Additionally, these ecosystems struggle to address deep-rooted distributive conflicts in water management [3]. Another persistent hurdle is balancing local autonomy with the need for cohesive regional action [12].

To provide a clearer perspective, the following table compares the key attributes of these models:

Dimension | Watershed Governance Forums | Implementation-Focused Ecosystems | Hybrid Collaborative Ecosystems |

|---|---|---|---|

Governance Structure | Informal and networked; promotes consensus over gridlock [6] | Project-specific with defined technical authority [2] | Dual-layered with regional oversight and local input [12] |

Stakeholder Inclusion | Broad engagement fostering social capital [3] | Moderate inclusion focused on technical and financial goals [2] | Broad engagement across multiple stakeholders [6] |

Implementation Capacity | Limited by political and legal barriers [6] | High capacity for targeted projects using tools like municipal bonds [2] | Effective through coordinated multi-agency efforts [12] |

Measurable Outcomes | Intangible gains in dialogue and shared understanding [6] | Tangible results measured in water volumes and cost-efficiency [2] | Mixed results, balancing measurable outcomes with intangible improvements [6] |

Key Limitation | Financial risks for disadvantaged partners [2] | Tension between local independence and regional cohesion [12] |

Conclusion

Each model for water management comes with its own set of trade-offs. Governance forums are particularly effective at fostering trust and encouraging dialogue, yet they often falter when it comes to resolving disputes over fair water distribution. As researchers Giorgos Kallis and Richard Norgaard have pointed out, collaborative governance alone cannot completely address these deep-seated conflicts [3].

On the other hand, implementation models prioritize measurable outcomes. For instance, infrastructure partnerships in the Tulare Lake Basin have achieved notable improvements in water supply [2]. However, these gains often come at a steep cost - over $1,000 per million gallons for underprivileged partners - raising serious equity concerns [2].

Striking the right balance in partnerships is key. Research indicates that partnerships with 16 or fewer members tend to maintain costs below $200 per million gallons. In contrast, those with 24 or more members frequently impose significant financial burdens on at least one partner [2]. This highlights the close relationship between partnership size and financial risk. Additionally, infrastructure projects designed to maximize partner benefits can inadvertently reduce water availability for non-partners, potentially leading to legal disputes that double transaction costs [2].

Advanced modeling tools offer a way to optimize partnership outcomes. A clear example comes from the Friant Contractors' $50 million investment in the Friant-Kern Canal rehabilitation in 2021. Using sophisticated modeling, alternative partnership structures were identified that delivered 58% greater water gains while reducing financial risks [2]. This underscores the critical role of data-driven tools in crafting effective partnership strategies.

Such tools turn complex design insights into actionable plans. Firms like Council Fire play an essential role in these efforts by providing the technical expertise needed to evaluate thousands of partnership scenarios. They utilize network analytics to pinpoint high-impact management opportunities and facilitate stakeholder collaboration across various levels, from consultation to co-creation [5]. By aligning financial goals with environmental and social priorities, these consultancies help organizations turn ambitious sustainability plans into practical, measurable results.

The key lies in setting realistic goals and adopting a middle-out modeling approach that balances strategic vision with technical precision. Organizations that emphasize inclusivity, proactively address third-party impacts, and leverage advanced analytics can create more resilient and equitable water management systems. These systems are better equipped to handle the challenges of climate uncertainty and meet the evolving needs of diverse stakeholders.

FAQs

What are the key differences between governance forums, implementation-focused ecosystems, and hybrid collaborative ecosystems in water management?

Governance forums serve as essential platforms where policymakers, regulators, and influential stakeholders come together to align on shared objectives, establish legal frameworks, and delegate responsibilities. These forums emphasize strategy, accountability, and open communication rather than hands-on project management. They typically operate under formal agreements or regulations, ensuring a structured approach to collaboration.

On the other hand, implementation-focused ecosystems operate at a more hands-on level. These bring together agencies, nonprofits, and private organizations to carry out specific initiatives, such as watershed restoration or stormwater management projects. Success in these ecosystems is gauged through measurable results, defined timelines, and performance indicators. Partnerships within these groups often evolve as individual projects are completed, reflecting their dynamic nature.

Hybrid collaborative ecosystems merge the strategic focus of governance forums with the operational strength of implementation ecosystems. These partnerships foster shared decision-making within project teams, allowing for a balanced approach to resource allocation, risk management, and financing. By integrating these elements, they work toward practical, long-term water solutions. Organizations like Council Fire play a pivotal role in these ecosystems, bridging the gap between policy objectives and actionable projects while ensuring that environmental, social, and financial goals are addressed cohesively.

How do collaborative ecosystems help smaller partners manage financial risks in water management projects?

Collaborative ecosystems in water management projects provide a safety net for smaller partners by spreading costs and responsibilities among public, private, and community stakeholders. This shared framework ensures no single entity shoulders the entire financial burden, making it more feasible for smaller organizations to engage and contribute.

Key strategies within these partnerships include tiered financing mechanisms, such as low-interest loans, grants, or repayment plans tied to revenue. Additionally, regionalization strategies play a vital role by pooling resources from multiple communities, creating efficiencies that reduce costs. Public-private partnerships (P3s) are another effective model, offering access to external funding, technical expertise, and steady revenue streams. These partnerships enable smaller utilities to upgrade infrastructure and meet regulatory standards without overwhelming their budgets.

Council Fire works with organizations to navigate these collaborative ecosystems by facilitating stakeholder engagement, aligning financial goals, and crafting communication strategies that highlight mutual benefits. This approach helps ensure smaller partners maintain financial stability while actively contributing to more sustainable and resilient water systems.

How do data-driven tools enhance collaboration in water management partnerships?

Data-driven tools are reshaping how water management partners work together by turning fragmented information into clear, actionable insights. These tools make it possible to monitor water supplies, identify problems, and evaluate conservation efforts in real time, promoting both transparency and efficiency across the board.

Technologies such as modeling systems and decision-support platforms are particularly valuable in assessing potential collaborations. They provide insights into compliance challenges, weigh cost-benefit scenarios, and evaluate risks, helping stakeholders make informed decisions. Additionally, these tools enable the exploration of solutions that effectively balance financial considerations with responsible water resource management. By adopting these technologies, organizations can forge stronger, more adaptable partnerships that align environmental priorities with sustainable long-term outcomes.

Related Blog Posts

FAQ

What does a project look like?

How is the pricing structure?

Are all projects fixed scope?

What is the ROI?

How do we measure success?

What do I need to get started?

How easy is it to edit for beginners?

Do I need to know how to code?